It's news to you, but to a copy editor, it's just the same old story

I was a part-time newspaper copy editor for 17 years, beginning

in 1980. This is a fictionalized account of that experience.

(2011) The newspaper’s “metro room” seemed designed expressly to spare reporters the sights, sounds and smells of real life. It used to be that if you were writing the weather story, you could look out a window to ensure that your account had some relationship to the actual out-of-doors. But all the windows had been covered for better "climate control,'' so you relied on the telephone “weather line” and wire service forecasts that might well say ``cloudy, windy and cold today,'' when in fact it was clear and sunny.

The erotica boutique across the street had long-since been replaced with a parking terrace whose heated stairwells were kept free of the homeless by a storm trooper-style security operation. The tavern and the poverty law center downstairs were also casualties of gentrification, having made way for a sleek, minimalist outfit called ``EuroDesign Associates.''

in 1980. This is a fictionalized account of that experience.

(2011) The newspaper’s “metro room” seemed designed expressly to spare reporters the sights, sounds and smells of real life. It used to be that if you were writing the weather story, you could look out a window to ensure that your account had some relationship to the actual out-of-doors. But all the windows had been covered for better "climate control,'' so you relied on the telephone “weather line” and wire service forecasts that might well say ``cloudy, windy and cold today,'' when in fact it was clear and sunny.

Where reporters had once scrambled out at the sound of sirens, crashes, booms and screams, they now reposed in a surreally quiet suite that insulated them from anything short of a major earthquake or direct nuclear attack.

The erotica boutique across the street had long-since been replaced with a parking terrace whose heated stairwells were kept free of the homeless by a storm trooper-style security operation. The tavern and the poverty law center downstairs were also casualties of gentrification, having made way for a sleek, minimalist outfit called ``EuroDesign Associates.''

As a liberal, and a defender of truth and the First Amendment, Chester Taft deplored all this ruthless sanitizing.

But as a sixty-year-old man teetering at the edge of a psychological abyss, he was grateful to the core that he could spend his days in a sterile capsule, where blood and guts, torture and terror, were just words sitting quite harmlessly on a page.

TIDYING UP A MESSY TUMULT

Taft would have preferred to stay in bed, hiding under the covers and listening all day to the classical music station. But for thirty-five years, he had allowed the messy tumult of daily news to lure him to the office, where – as a copy editor – he would try to make it reasonably coherent for the paper’s readers, who probably wouldn‘t have noticed either way.

Surely, during the night, there had been typhoons leaving thousands homeless, a coup or two, an anti-gay crusader got nabbed in a gay bar, the defendant in a massive fraud scheme committed suicide, or the ozone layer had packed up in disgust and vanished altogether. Every morning, Taft took his place in the newsroom and dutifully fashioned another day-in-the-life of Earth into the tiresome but serviceable format of the inverted pyramid.

A lover of literature and Great Ideas, he had always regarded ``news'' as monstrously reductive of life. It was an artifice created to make money and to be an enabler of power. It was the “life” of press conference and staged event, of jutting chins, jousting, lying, leaking, and petty jockeying. News was propaganda, and media bestowed an air of objectivity and legitimacy on whatever storyline their wealthy owners chose to support. More than anything else, news was the continuing saga of testosterone, a nasty fluid that brought ruination to marriages, countries and the Earth itself.

Man's newspapers mocked him as god and nature could never hope to do. In their tidily arranged 12-pica columns, they represented the penultimate portrayal of human activity as neurosis.

THE IRONY AND THE EXISTENTIALITY

As he drove to the office, he mused at how ironic it was that an existential character such as he would soon be ensconced in a milieu that actually exaggerated the absurdity of life -- the shallowness, the sham, the futility of it.

Of course, there was real life out there, outside the dandified, white-gloved routine of the newsroom: He could be ministering to the poor ( “Chester Taft, director of the Glory Road Soup Kitchen and Shelter, today angrily denounced the Senate Human Services Committee. . .''). He could open a friendly, coffee-scented used-book store (free GED tutoring in the loft), or be a residents' advocate in a nursing home. He could even make some friends.

When he thought of this on melancholy afternoons, his duodenum went into spasm as the old song ``It Hurts to be in Love'' wailed through him. Taft was manic-depressive. As long as his life was routinized and detached, the depressive force presided, ranging from an unkempt vegetative state on weekends to quasi-functional unhappiness while he was at work.

But if he permitted something to interest him, to capture his heart or rally his conscience, he paid dearly for it.. The manic phase slammed him like the fist of God, putting him back in his place. His heart raced, his hands shook, he stammered. He had energy and expansiveness, he was hopeful and brilliant, but it had the taste of a taunting and treacherous drug. He couldn’t sleep. He was raw and reckless. Inevitably, he crashed

Sad but true: He belonged at the newspaper, where he could immerse himself in communiques from envoys, cliff-hanger rescues, casino fires and filibusters. He loved mankind by refining the poignancy of human-interest articles and composing soul-wrenching headlines about the various forms of mass murder, including war, weather, religion, disease, tyranny and television. This he was able to do from the safety and serenity of the copy desk.

BEING AT THE HELM OF HISTORY

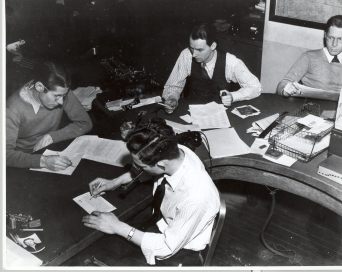

Looking at the copy desk from across the newsroom, one might think of a wax-museum set piece, portraying a bland and joyless blackjack game. Around the U-shaped table sit six people; inside is the “slot man,'' who deals out the out stories to be processed. At first glance, it might appear that what goes on here is a dull and sedentary enterprise, moles scratching absently at the shreds of paper that flow by -- limp-wristed rodents, squinting and licking their pencils and scratch-scratching harmlessly in the corner. The hunched modesty of their demeanor belies the truth: that this is a bona fide fiefdom with a troubling secret. It is here, not in the newspaper’s board meetings or editors' huddles, that policy is made and history conveyed.

The copy desk is the bespectacled, shirt-sleeved little man behind the majestic, oracular Oz that is the newspaper.

As grandiose as it may sound, being on the copy desk feels like being at the helm of history. The crashing of the waves is senseless, to be sure, but for eight hours, Taft will be awash in dramatic distractions. He had stopped hoping long ago for anything more.

A NEW DAY BRINGS NEW NEWS!

Taft arrived thirty minutes early, as always (to make sure he wasn’t late) and prepared himself for the day's work with the vain urgency of a surgeon getting ready for an operation. He went to the restroom and scrubbed down vigorously, for although his task was not exactly hygienic, it seemed fitting that one's hands should smell like soap prior to smelling like blood. He pulled his shoulders back and rotated his head like an ecstatic dervish to relax his shoulder muscles and flood his head with oxygen. Then he strode to his ``station'' at the copy desk and joined the others in the silent ritual of laying out their instruments of delicate butchery: sharpened pencils, varicolored felt-tipped pens -- lined up to the right like scalpels -- scissors aligned perpendicularly, flanked by tape and paper clips. To the left was the intricate chart specifying headline and photo counts, and between each station were stacked the dictionary, AP stylebook, thesaurus and other references of the trade.

Taft's colleagues awaited the onslaught of articles with downcast eyes, prayerlike. There was a pleasing, ever-moving intimacy in this pre-dawn gathering -- something fragile and exposed about people who had so recently awakened and ventured into the dark, as if for some emergency, and a kind of shared trust at being seen in such a condition. As 6 a.m. approached, Taft tossed off the last of his coffee like an opera star gargling before the curtain. The flood of news copy would soon begin, and with it the intense race to get first edition out.

First edition of the newspaper would be on the stands by noon. “Getting it out'' (which had always sounded to Taft like having a bowel movement or overcoming a stutter) involved a variety of macho rituals: rip it, cut it, slash it, (or even kill it, but if not,) spike it, punch it and finally tube it (into that pneumatic snout, which hurtled it away never to be seen again until it had achieved the magical legitimacy of print). This was wholesale slaughter, and so early in the morning.

How regrettable, the demise of linotype machines, which had made such solid, muscular noises and produced hot, oily metal type. That was printing that seemed to have a respect for the substance of what was printed. The medium was indeed the message, and the message these days was as fleeting as youth.

Throughout the office, old newspapers were heaped in bins reminiscent of the garbage cans in a high school cafeteria: So much effort had gone into the preparation, but moments after it was served, there it was, dumped and rotting, irrelevant already..

BROUGHT TO YOU BY: PALE, CLUELESS KIDS

The young reporters plinked away with vacant eyes at their typewriters, made phone calls and (if it was absolutely necessary) loped out to ``cover stories.''

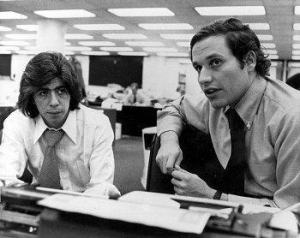

(In bygone days, when Taft first entered this sleazy business, the reporters may have been hacks, but at least they had some bravura, some blood and bourbon, in their veins. They were out there digging up the dirt. They hung out at City Hall and the Capitol. They sat through all those council and committee meetings in which things actually got decided. They had beats, and they covered them with ardent, saavy territoriality.

These anemic kids, whose style, if they'd ever had any, had been maimed beyond recognition by journalism school, were cool technicians who, lacking the guts and conviction to DO anything, instead sat there all day, writing either blandly or gushingly [depending on several criteria] about those who did. Taft, who lacked the guts and conviction even to write, tidied up the mess they inevitably made of even the most straightforward head-on collision.)

Things looked pretty dull in Reporterville at the moment, but the sun wasn't even up yet. Maybe the Chamber of Commerce would send croissants and gourmet coffee over ``with deep gratitude'' for the paper's ``hearteningly fair'' stories about the group's downtown-beautification proposal, currently before the City Council. Or perhaps McDonald's would dispatch a crew of teenagers dressed as vegetables to publicize its forthcoming salad bar. That would undoubtedly land them a big B1 feature -- with color art if they distributed a few dozen Happy Meals (upholding the First Amendment leaves one perpetually famished).

NEWS AS PRODUCT PLACEMENT

If this were really a lucky day, a former Miss America (better yet, the Playmate of the Year) might appear, expressing her profound devotion to a new line of skin-care products or exercise equipment. Get those pens out! The people have a right to know! And get an autographed picture (for your kid sister) (and a few extras for other people with kid sisters). The circus was due in town; that muscular, half-nude animal trainer was bound to show up again with a lion or a chain gang of monkeys. Last year, they'd wound up on A1 -- above the fold!

One of those ruddy, four-star generals with a voice that made your breastbone vibrate might return to restate -- with thrilling passion-- the need for ``continued vigilance'' in the national-security arena by the world's ``star-spangled beacon of hope.'' Kevin Bacon or Demi Moore could very well turn the newsroom into a swooning uproar by dropping in to discuss their latest cinematic ``labor of love.''

The State Bankers Association would call any minute, probably, with an all-expense paid trip to its convention in Sun Valley for the guy on the business desk. Mickey, Goofy and Donald might break-dance in just when things were starting to get boring again, to hand out T-shirts and sherbert-colored visors heralding the latest Disneyland attraction.

And that, guys, was news! Reporter-friendly news: It frolicked right up to your chair, chirped forth with calculated quotability and handed you a cleverly worded fact sheet in case you were too pooped to take notes (with color glossies attached, in case the photographers were too pooped to take pictures).

Making the world safe for free expression is exhausting, but it sure gives you a warm feeling in your tummy at the end of the day, when you head out for drinks with the president of the department-store chain that's having those irritating labor troubles.

HEARTSTRINGS AND HALOES

In the meantime, many of the reporters were undoubtedly dashing off the paper's stock-in-trade: saccharine tales of heroes and tragedies, prayers and miracles, embraces and tears. They knocked these things out so blithely that the veterans (who had reached the ripe old age of 25 or so) sometimes forgot to gloat over all the heartstrings they would touch. That was one of their favorite words: heartstrings. God!

Their rationale was, ``Readers eat this shit up.''

``Woodruff, line two. It's the governor.''

Chalk up one more brownie point for the new kid. Reporters courted rich, famous and powerful sources; sources courted them in return. Christmas ``gratuities'' and dinner-party invitations flew back and forth. Everyone snuggled happily in everyone else's pockets, thrilled at being so well-connected and so fondly regarded by people of influence. In with the in-crowd! Dancing cheek-to-cheek! Is being a grown-up cool or what?

Few reporters were introspective enough to realize that they were doing the grunt work of warmongers, political opportunists and the captains of profit, but in fact that was their chief function. Yes, even in America! Journalists were not Seekers of Truth but rather conduits for elaborate fictions, the fictions that kept the many paying and the few raking it in.

WTF: WHAT THE FLACK?

It didn't take long before the office, agency, utility or industry that the

reporter was ``covering'' offered him a job in public relations, and so he soared off to be a flack, which is what he should have been all along. What he HAD been all along. The paper replaced him with another kid right out of college, and the process began again. Thus did newspapers serve as the finishing schools for Power's apologists.

And when each eager young thing showed up back at the newspaper to plead his new boss's case over an expense-account lunch at one of the toniest places in town, he was welcomed like a brother and guaranteed ``great press.''

On the other hand, reporters literally hid in the bathroom from the ``kooks'' who opposed the grand designs of the Establishment. These so-annoying people would show up with page after page of “documentation” about some pollution thing, or some little exchange of money involving a lobbyist, whatever. They just didn’t get it: The reporters didn’t care! They did not appreciate this complexity, this duality, these attacks on bigwigs who were bigwigs for a reason.

The only ones who cared about that stuff were the occasional reportorial malcontents, inspired by Woodward and Bernstein, who aspired to be ``watchdog'' journalists. Arf, arf!! Crusaders were so annoying. So negative, so disrespectful! Investigative: What an abrasive word. These guys must come from very troubled homes, or something.

IF YOU WANT TO DIG UP DIRT, PLANT A GARDEN

They hadn’t gotten the message: Don't step on any (important) toes, kids.

The muckrakers were usually rather unkempt too -- how embarrassing for their stylish colleagues. Shaggy hair and baggy pants! They wore old running shoes to interviews! Where were their loafers?

Thank goodness those probing types -- with their file folders spilling over with notes, scandalous documents and pointed questions -- fled, generally to one of the bleeding-heart rags in the East, once it became clear that everything they wrote would either be castrated or killed.

The editors would much rather deal with the dozens of press releases that came in each day -- most of which would make it into the paper virtually unchanged, no matter how self-serving -- because a paper's got to have some ``copy'' to fill the ``news hole'' (what's left after the ads are jammed on the page) and why pay to have a decent-sized staff when this stuff piles in for free?

Every morning, the city editor loudly prayed that there would be no breaking news today. Actual events were such a hassle, and after generations of journalism, real-life occurrences still rudely refused to respect press deadlines. Thus, the considerately scheduled political announcements or ribbon-cuttings were the paper's mainstay.

Over in the conference room, the caved-in old men of the editorial board -- who managed to be sourpusses and pollyannas at the same time -- agreed as usual that there wasn't much to say today (unless welfare payments to all those good-for-nothings were increased or the steel mill was fined for polluting again, in which case they would be in a militant mood indeed).

THE SHRINE THAT SPEWS

At the far end of the room was the cubicle containing the wire machines, each of which represented a different news syndicate. The cast-iron monoliths churned their guts out with the crazed and mournful rhythms of the human condition, day and night, furiously and unregaled, humming and chugging like the life-support system of the universe, and pouring forth with dispatches from around the world.

To Taft, the wire room was a particularly poignant microcosm as it wretched with the throbs and trumpetings of a whole species in a room that had a heavenly, golden glow. Some gesture of respect should be shown: an attendant in white Gandhi pajamas, perhaps, who would at least pretend to monitor and minister to this global gut-spilling, this relentless hara-kiri, or candles and flowers, or a piece of secular-humanist statuary atop each of the machines, which are both cradle and grave to events-as-news.

But no one was in there to weep or applaud as battles were lost, cures discovered, landmark verdicts rendered -- except when one of those handicapped copy kids (the paper's concession to affirmative action) -- rolled or hobbled in to ``rip the wires'' so the editors could glance through them and decide what the ``good stories'' were. Or when the bell went off and someone rushed in to see whether it was World War III or the new Junior Miss that was being announced.

SOURCE CLAIMS REAL POWER RESIDES IN SECRET CABAL!

Copy editing offered to Taft the power of a high-level management job without the hassle of petty organizational politics, ass-kissing and struggles for consensus. It also provided an outlet for the nit-picking schoolmarm side of his personality, rewarding it with one vindictive triumph after another. He made decisions all right -- every particle of every article was subject to his change -- by fiat, not committee. If he thought something was boring, inappropriate, self-evident, inflammatory, inelegant, unfair, or too sappy even for this particularly sappy newspaper, he just slashed it out, and that was that. Voila! His mood, as well as his values and aesthetics, were as much the substance of the news as the facts were.

If someone he liked, Eleanor Holmes Norton or Ralph Nader for example, made a grammatical error, Taft corrected it. If Dan Quayle or David Duke slipped up, Taft left it alone -- or found some way to highlight it, if possible.

And he didn't feel the slightest bit guilty about it either; the other side (all those right-wing, warmongering wackos) had plenty of its own operatives out there trying to win hearts and minds by any means necessary. Taft was just doing his part to advance what he viewed as The Good. His power to give events any slant, moral sense, or personality he pleased left him both giddy and solemn -- and tacit, as if he had taken an oath of silence about his awesome authority.

Thus this:

Women's libber Gloria Steinem was characteristically strident as she denounced men's magazines for their ``exploitation of women.'' The aging radical, who still goes braless, wore a T-shirt and faded dungarees to address a young executives' group at the posh Lindon Hotel.

Became this :

Women's liberation champion Gloria Steinem today forcefully denounced men's magazines for their exploitation of women. The longtime social activist, still regarded as a key figure in the realm of human rights, addressed a capacity crowd of young executives at the Lindon Hotel.

And this:

The president Tuesday strode through a group of MIA families, comforting each with warm assurances about the administration's commitment. The president, tanned and smiling, was accompanied by staff and Secret Service personnel.

Became this:

The president Tuesday ambled through a group of MIA families, repeating over and over again the administration line that ``appropriate'' efforts are being made on their behalf. Secret Service personnel provided tight security.

And this:

Informed sources said South African police defended themselves from a teeming mob of blacks with automatic weapons today, but the highly trained personnel averted major tragedy, killing only two and wounding less than a dozen of the screaming demonstrators.

Became this:

Informed sources acknowledged another two black apartheid protesters were killed today and some 12 wounded as riot-equipped South African police fired into an unarmed crowd in the escalating rights struggle.

And this:

The swarthy, costumed PLO leader ranted and gesticulated wildly, conjuring up every perceived inequity his alleged constituents had ever faced. The Security Council responded with glum silence.

Became this:

The traditionally garbed PLO leader presented an impassioned, animated history of his people's victimization as the Security Council listened intently.

THE HYENA’S RED TEETH

Taft experienced a sort of guilty sensuality as he sliced away with his red pen. If someone had interrupted him unexpectedly, he would have jerked up, shamefaced as a hyena caught gnawing at another animal's prey. But oh, how good it tasted!

Copy editing was a rushing stream of victories each day, a droll, stately assertion of authority. His job was a cunning hover-and-pounce, hover-and-pounce; he leapt boldly at errors, clarified ideas and replaced flaccid words with images vibrant and powerful. It was a craft -- a scrupulous sculpting process, a painting of pictures, a weaving of spells. It was a muscular quest for both order and color. It was a dignified outlet for his aggression: He was The Slasher, disguised as a mild-mannered man.

SCREAMING RAIDS AMID THE PAPAYA TREES

Moreover, he could do it without the embarrassing futility of being an actor, out there, in the ``real world'' that made ``news.'' He could do it without joining the obsequious hordes of journalists, who trounced along, strewing flowers along the path of power and profit. Taft remained magisterially at his station -- the bemused gatekeeper for whatever strands of truth and significance their stories inadvertently contained.

He was post-production director, in a sense, of an often poorly scripted show -- excising repetition, superfluity, pomposity, incoherence; inserting pan shots and transitions; tightening up the action. He was transported to far-flung hamlets and archipelagos, parliaments, back rooms, gang hideouts, mountainous rebel outposts, steamy jungle ecosystems . . . to places like Usulutan, where Captain Baltazar, with his guerrilla force Farabundo, waged screaming raids amid the papaya trees. These things were really happening! At least, that’s what the journalists were telling us, probably while lying out by a pool, drinking tropical concoctions and making it all up. Their rationale: I’m not going to risk my life -- it’s a jungle out there!

This was a job in which it seemed appropriate to shake one's head, grunt, chuckle, snort, cluck, sigh and curse all day, as one pored over the anecdotes about this bizarre creature called man. As Taft read through the raw copy, fresh from the wire machines, he felt as if he were the first to know, and now he's got to break the news to everyone else. (What a responsibility!)

So deeply involved did he get that he developed a proprietary feeling about each article he handled: If a neighbor were to say ``Did you hear about that sniper in Wisconsin?'' Taft would respond, ``Yes, that's my story.''

Like the most disciplined of writers, Taft had sat here at his desk every day for his entire adult life, working at his craft. Not one byline did he have to show for it, no portfolio, no awards. His magnum opus could be twirled out, player-piano style, on a microfilm screen, an epic poem consisting of headlines that conveyed the saga of decades of human history. If he were to string it all together, he might well be designated the Homer of news, a secular mystic whose filtering of modern life made it all seem heartbreaking, heartwarming, worthy of living through.

A HEADY REVERIE

Writing a headline was a bit like gift-wrapping or garnishing a story. You let your mind billow over it and waft through its implications, inhaling its bouquet as it swirled over the intellectual palate, probing for a compelling peg.

Then, with hands poised like a pianist, eyes off in the momentous distance, visions of events swirling in the brain, whirlpooling downward, you distilled it into something lean and singularly evocative, playing it out on the keyboard, swaying to its music. It was here that the action that had been reduced to language was synthesized into meaning, given shadings and tone.

Taft's headlines lilted with rhymes, reveries, similes, spoofs and metaphors. Like poetry, headlines were a commando art form, a hit-and-run exercise for a hyperactive mind that had no patience with painstaking explanations and chronological accounts, but preferred bright, rapid bombs of insight.

Taft could give government majesty, issues urgency, commerce vitality and existence in general a tender irony that was, it seemed, a humane thing to do, even though it almost always required lying. He could lace life with lyricism, pruning down (and elevating) to haiku the affairs of man, turning out masterpieces with a paint-by-numbers kit, conveying all the nuances of history-in-the-making within the staccato confines of a headline-count chart.

IF YOU WANT TRUTH, GET IN BED AND DREAM

Taft never discussed the disquieting truth he had come to know about newspapers: Seeing the news as he did each day, on bits of paper filled with errors, seeing the constant corrections coming over the wires, seeing the contradictory versions -- the wildly disparate facts and figures and slants and sympathies -- reflected in different accounts, and mindful of what he himself could do to mold ``facts,'' Taft knew that the ultimate product -- despite its air of authority -- was grossly flawed, if not downright irresponsible. If it's truth you want, Taft would tell you, read fiction or poetry (even there, the truth is between the lines), or get in bed and dream.

Still, his pride and pleasure in his own technical competence were engaging enough that he generally forgot, while he was in the thick of things, that he was contributing to -- and living off of -- a sham of mind-boggling proportions. ``Poor old basket weaver,'' he would think as he came to, patting his own pale hand.

NONE OF THIS MATTERS, MY FRIENDS!

A few times a year, somebody actually yelled ``stop the presses!'' but all that meant was that an advertiser or a golf pal of the publisher (or someone from his lodge, church, neighborhood or one of the many boards on which he served) had gotten wind of a ``potentially embarrassing'' or ``misguided'' story. Kill it, fill it, roll them presses once more.

Putting out a paper was, to Taft's way of thinking, as futile as cleaning you house: It had to be done over again in no time and, in any case, who cared? Dirt and disarray, whether globally or in your closet, naturally seek a certain plateau and basically stay there, fluctuating just enough to distract you from the real issues.

Taft spent his days -- diverted by his craft and by the pressure of deadlines -- producing a product of diversion for others. If he could have chosen the newspaper's masthead, it would have proclaimed: ``None of this matters, my friends!''

But perhaps they knew it. Perhaps, to them, each day’s news is just another installment in the very bad movie called “Human History,” a movie whose premier flaws are exasperating repetition and a lack of believability.

Every year, it was the same stories: of holidays -- with their attendant speeches and parades -- awards, from Grammy to Nobel -- beauty pageants, Superbowls, Daylight Savings Time's comings and goings, Great American Smokeouts, the tiresome Jerry Lewis telethon, endlessly notable anniversaries (Pearl Harbor to moon landing to Elvis' birthday), commencement speeches and political campaigns.

Every day there were monsoons and mudslides, car bombs and chemical spills, babies with bloated stomachs and flies in their eyes, record-breaking drug busts, buses filled with barefoot people lurching down tropical ravines, trains derailing, mothers picketing, plants closing, borders shifting, new underdogs emerging, entire species vanishing, pillars of the community scandalizing, manufacturers recalling, quiet loners slaughtering, cease-fires ceasing, intelligence agencies trampling, legends dying and high-level sources speaking, on condition of anonymity. Stunning new medical insights were announced, and within months, stunning contradictory data emerged.

BACK IN THE REAL WORLD, DEATH SAYS ‘THERE YOU ARE!’

It was a beautiful afternoon, but for Taft this was just a taunt from above as his rotating stage set geared up to groan into evening. Out here, in the real flesh-and-blood world from which the newsroom was ironically such an effective refuge, everything was drenched with death. It was not himself in the grave that obsessed Taft, although the thought of it caused his stomach to clamp up as he imagined lying down there while seasons streamed silently overhead, fast-forward, forever.

What obsessed him was the death that raged through a spring day like today, the death that was planted already in a child, that entwined an embrace, that framed a tradition, that colored the crescendos of music, that hovered almost visibly in a photograph. It was the silence at the heart of things that mocked all sound, all beauty, all life.

Bald sadness and tragedy Taft could handle. It was the poignancy of everything else that tore him apart.

When he got home, he poured himself a drink and, as usual, tried to think of something meaningful to do before dinner. When your work day begins at 6 a.m., you do have a gaping void before it becomes civilized to eat yourself into a dinnertime stupor. After all these years, he had never stopped fantasizing about possibilities, but they never seemed compelling enough to get him out of his recliner. Plus, it would be cruel to disturb his cat, Katmandu, who was snoozing so comfortably in his lap, while Catalina sprawled out nearby. He closed his eyes and kept on drinking.

At last, the afternoon was over. It was almost time to face the hushed derangement of dusk, the gratuitously cruel chiming-in of stars, the expressionless moon.

A sunset the color of Thousand Island dressing poured itself behind the horizon, lifting its fingers in bittersweet farewell. Taft went out to get the newspaper from the lawn and opened it absently while he ate some bread and cheese. There he was, sprinkled among the pages: poetic, ferocious, fleeting. Even as the metro edition of the newspaper hit the porches of tens of thousands of homes, his day, his work, his life was dying -- superseded already by the stomp of time. Food, not yet for worms, but soon for the fireplace, the trash bin, the transient who would use it to warm his feet after being kicked out of the parking -terrace stairwell. Taft almost yawned but, on second thought, shuddered.

Night had appeared, ready to stalk him again. Bed beckoned like a womb and torture chamber combined: his only reality, his ultimate truth.