Wesley Gordon Bowen, 1924 ~ 2003

Wes Bowen roared up to the entrance of Olympus High School in a spanking-clean van that had a large full-color painting of his face on each side of it and, in bold lettering, "Bowen, and All That Jazz."

Wes, a renowned radio personality throughout the Intermountain West, "had the voice of God, if there were a God," as one of my friends had put it. His tone was deep, rich and oracular.

So when he leapt out of the van, in a cloud of Aramis cologne -- his apricot-colored ascot scarf fluttering in the breeze -- and showed himself to be almost diminutive, it was a bit of a shock.

Wes, a renowned radio personality throughout the Intermountain West, "had the voice of God, if there were a God," as one of my friends had put it. His tone was deep, rich and oracular.

So when he leapt out of the van, in a cloud of Aramis cologne -- his apricot-colored ascot scarf fluttering in the breeze -- and showed himself to be almost diminutive, it was a bit of a shock.

But when he opened his arms to us and boomed, “So good of you young ladies to invite me! You‘re delicious!” he immediately became the larger-than-life character we had expected. He wore a handsome, tweedy suit. His skin had a healthy, well-oxygenated glow, and his hair had been faintly tinted to match the ascot. His wry, discerning face reflected the massive intellect that we knew he possessed.

If Wes hadn’t died -- suddenly and unexpectedly -- in 2003, he would be 87 next month. In my brain, he is still very much alive. We met on that day when I was in high school and remained close for the next 40 years. Our friendship was the longest and dearest of my life.

My mind became so full of Wes’s exclamations, admonitions and witticisms that I still see and hear him every day, and I quote and refer to him regularly. The only person who has had a greater impact on me is my mother.

WES GIVES A CLASS IN ‘CLASS’

As president, in 1966, of the Symphony Sub Debs -- a horribly boring school club -- I had hoped to "jazz things up" by inviting this notoriously brilliant and cosmopolitan radio star to speak at an after-school forum about "one of America's greatest cultural achievements and exports to the world."

He was witty and debonair from the moment we met, but what came next showed what an incredibly classy man he was.

The auditorium was essentially empty. There were about five people sitting in the front row, each of whom I had begged to attend. I felt humiliated and guilty. Obviously, my concept of what might draw a crowd had been terribly wrong. How could no one care about jazz? Actually, I didn't care about it either, but I was hoping to, because it seemed like a cool thing to care about. The Beatles and Beach Boys were great, but we were 16 years old, and it was time to acquire some mature tastes. It was time to be hip, not just "cute."

Wes displayed no irritation or disappointment whatsoever at this ridiculous situation: a vast, dark auditorium devoid of anything deserving of the term “audience.” He marched right up onto the stage, stood behind the lectern, and gazed out magisterially, as if the room were filled with the cream of society. He proceeded to give a magnificent, hour-long lecture on the history and influence of jazz. He had no notes. He was funny, and he was dramatic, and he didn‘t sugar-coat the harrowing racial environment in which jazz was born. He conveyed a passion for the depth and humanity of jazz music that I'm sure no one there ever forgot.

If Wes hadn’t died -- suddenly and unexpectedly -- in 2003, he would be 87 next month. In my brain, he is still very much alive. We met on that day when I was in high school and remained close for the next 40 years. Our friendship was the longest and dearest of my life.

My mind became so full of Wes’s exclamations, admonitions and witticisms that I still see and hear him every day, and I quote and refer to him regularly. The only person who has had a greater impact on me is my mother.

WES GIVES A CLASS IN ‘CLASS’

As president, in 1966, of the Symphony Sub Debs -- a horribly boring school club -- I had hoped to "jazz things up" by inviting this notoriously brilliant and cosmopolitan radio star to speak at an after-school forum about "one of America's greatest cultural achievements and exports to the world."

He was witty and debonair from the moment we met, but what came next showed what an incredibly classy man he was.

The auditorium was essentially empty. There were about five people sitting in the front row, each of whom I had begged to attend. I felt humiliated and guilty. Obviously, my concept of what might draw a crowd had been terribly wrong. How could no one care about jazz? Actually, I didn't care about it either, but I was hoping to, because it seemed like a cool thing to care about. The Beatles and Beach Boys were great, but we were 16 years old, and it was time to acquire some mature tastes. It was time to be hip, not just "cute."

Wes displayed no irritation or disappointment whatsoever at this ridiculous situation: a vast, dark auditorium devoid of anything deserving of the term “audience.” He marched right up onto the stage, stood behind the lectern, and gazed out magisterially, as if the room were filled with the cream of society. He proceeded to give a magnificent, hour-long lecture on the history and influence of jazz. He had no notes. He was funny, and he was dramatic, and he didn‘t sugar-coat the harrowing racial environment in which jazz was born. He conveyed a passion for the depth and humanity of jazz music that I'm sure no one there ever forgot.

“Stay in touch, luv,” he called out as he jumped back into the van. “I shall demand to be kept apprised of your trajectory.”

THE PULSATIONS OF DEAR WESLEY

It seems so quaint now, but back in the early 1960s, my parents, sisters and I gathered every night around the little radio in the master bedroom to listen to “Public Pulse,” a KSL call-in program that reached the entire Intermountain West. Wes discussed controversial issues with local, national and international figures, including Sir Edmund Hilary, former British Prime Ministers Edward Heath, Harold MacMillan, and numerous presidential candidates. He won award after award for the program, and was also renowned for his jazz programs, “Rare But Well Done“ and “Bowen and All That Jazz,” which were broadcast in 38 states and transmitted to ships at sea. He did a television interview program as well, and many years later, I would be his guest when I was on a national magazine tour.

Wes was thrillingly opinionated and fascinatingly foreign to our family as we immersed ourselves in “Public Pulse.” I think we were all in love with him, including my father, and we were all a little bit afraid of him as well. When a caller irritated him by being ignorant, boring or obsequious, Wes could be dismissive or even quite scathing. He had a high-class British accent, and a tone that veered readily from witty to ponderous, and a ravishing knowledge of history, from Greek and Roman times to the present. It is from him that I came to appreciate, while I was still in junior high school, the relevance of the past to the present. We all learned a lot from “Public Pulse,” about current affairs; about art, music and poetry; and about what a “life of the mind” entails. He was, indeed, the region’s Public Intellectual.

“Public Pulse” became a prototype for today's popular talk radio format, but Wes wouldn’t appreciate the comparison. His program was civilized and objective. There were no raised voices and no rants. It was an enriching dialogue presided over by the most complex and original man I have ever known.

LETTERS FROM SHAKESPEARE

Wes and I remained in touch following my high-school fiasco. After my first year at the University of Utah, I got a summer job in New York City, working for a brazenly unconventional advertising executive on Madison Avenue. I stayed at the Barbizon Hotel for Women, the same place where the doomed poet Sylvia Plath lived during her summer magazine internship, chronicled in The Bell Jar, which had not yet been published. The Barbizon, at Lexington and 63rd, is pictured below.

THE PULSATIONS OF DEAR WESLEY

It seems so quaint now, but back in the early 1960s, my parents, sisters and I gathered every night around the little radio in the master bedroom to listen to “Public Pulse,” a KSL call-in program that reached the entire Intermountain West. Wes discussed controversial issues with local, national and international figures, including Sir Edmund Hilary, former British Prime Ministers Edward Heath, Harold MacMillan, and numerous presidential candidates. He won award after award for the program, and was also renowned for his jazz programs, “Rare But Well Done“ and “Bowen and All That Jazz,” which were broadcast in 38 states and transmitted to ships at sea. He did a television interview program as well, and many years later, I would be his guest when I was on a national magazine tour.

|

| "Let's all hush now -- Wes Bowen is coming on!" |

“Public Pulse” became a prototype for today's popular talk radio format, but Wes wouldn’t appreciate the comparison. His program was civilized and objective. There were no raised voices and no rants. It was an enriching dialogue presided over by the most complex and original man I have ever known.

LETTERS FROM SHAKESPEARE

Wes and I remained in touch following my high-school fiasco. After my first year at the University of Utah, I got a summer job in New York City, working for a brazenly unconventional advertising executive on Madison Avenue. I stayed at the Barbizon Hotel for Women, the same place where the doomed poet Sylvia Plath lived during her summer magazine internship, chronicled in The Bell Jar, which had not yet been published. The Barbizon, at Lexington and 63rd, is pictured below.

Wes sent me a letter every week, hand-written on elegant, scented paper, and they were page after page of hilarity, morose brooding, luminous memoir, philosophizing and sociocultural critique as well as paternal advice. Each was a gem.

INFILTRATING THE MORMON SANCTUM

When I returned to complete my degree in Journalism at the U,. Wes designed an internship for me, which he grandly titled “Assistant to the Director of Public Affairs” at KSL Radio/TV.

It was ironic that such a profane man, who regarded all organized religion with utter contempt, was writing and voicing the editorials that represented the views of the Mormon-owned broadcasting empire and serving as Vice President for Public Affairs.

And it was equally ironic that I -- a devout atheist with a resentment toward what Latter-day Saint bigotry had put me through as a child -- would be drafting editorials right along with him.

I doubt that the Brethren knew who they were really dealing with. Wes’s parents were converted into the Church when he was a boy in South Wales, but he told me he regarded all organized religion as “repellent hogwash.” He and I were both very much to the left, politically and culturally, while the Church was very much to the right.

I doubt that the Brethren knew who they were really dealing with. Wes’s parents were converted into the Church when he was a boy in South Wales, but he told me he regarded all organized religion as “repellent hogwash.” He and I were both very much to the left, politically and culturally, while the Church was very much to the right.

Although his battles with KSL’s editorial board became the stuff of legend, he managed -- thanks to his personal charisma and powers of persuasion -- to both keep his job and influence the positions that KSL adopted on the most important issues of the day. Despite his differences with the higher-ups, Wes was truly fond of them.

I enjoyed researching and writing editorials at first, but it quickly became tiresome. To say, “KSL condemns the……..” or “KSL hopes all citizens will………” or “KSL applauds the children whose pennies made such a difference…..,” began to seem like a pointless exercise. It made me feel impotent, and I don't like that. Very little that we wrote, no matter how sensible and well-documented, had any effect on anything. So I remained in the job for the college credit, the paycheck and the priceless opportunity to get to know my very first Great Man.

STROLLING, STARRY-EYED, WITH CARY GRANT

As a 19-year-old, I was awe-struck by the fact that I got to hang out with Wes for three half-days a week. It was like having Cary Grant move in with you and become your bosom friend. He was such a bon vivant with so much savoir faire! (my French was finally coming in handy) He was an aristocrat, and he was a legend. The word “panache” was invented for this man! He was the romantic lead in a period piece about the glory days of the British Empire. He was my hero.

Walking around downtown with him, mulling ideas for our next editorial series, one would have thought that he had royal blood and royal powers. People descended upon us from all directions on Social Hall Avenue and on South Temple, as if to kiss his ring. He was very amused by all the adulation, and I think he secretly believed he deserved every damn bit of it. He was not at all oblivious to his magnetism.

“This is all becoming terribly cloying, don't you think? Let’s go get a bite,” he would say.

“This is all becoming terribly cloying, don't you think? Let’s go get a bite,” he would say.

We always wound up at the University Club, high up, overlooking the city, such as it was. He ordered two coffees and two massive sweet rolls, drenched in icing, with two pats of melted butter on top of each. My god -- and I ate it! How did that happen? When you were with dear Wesley, there was a devil-may-care contagion that occurred. You were in a zone of Magic in which calories did not count. (When we got back to the office, he always offered me a sweet, herbal pastille from the tin on his desk, just to get more sugar into me, and I never refused one.) To me, everything was in a shimmer, I felt so privileged to be his friend. I think he would have regarded me as his daughter, if he weren’t so profoundly in love with his actual daughter. He never failed to get teary-eyed, just mentioning her name.

So he told me his feelings for me were “avuncular.” That was just one of hundreds of words he used over the years that I had to ask him to define. He said, “Don’t mind me if I get a bit ribald.“ If it had been anyone else, I would have thought he was showing off. But Wes wasn’t -- he loved language, as I do, and he always wanted to use the perfect word, no matter how obscure it might be to the unwashed masses.

LONDON CALLING

After my third year of college, I was awarded a grant to spend the summer in London, studying the impact that immigration was having on British society.

Wes had been reared in England and went to the prestigious Queen Elizabeth’s Hospital boarding school for boys in Bristol, which is pictured below. He loved London and was delighted that I would experience his old stomping grounds.

INFILTRATING THE MORMON SANCTUM

When I returned to complete my degree in Journalism at the U,. Wes designed an internship for me, which he grandly titled “Assistant to the Director of Public Affairs” at KSL Radio/TV.

It was ironic that such a profane man, who regarded all organized religion with utter contempt, was writing and voicing the editorials that represented the views of the Mormon-owned broadcasting empire and serving as Vice President for Public Affairs.

And it was equally ironic that I -- a devout atheist with a resentment toward what Latter-day Saint bigotry had put me through as a child -- would be drafting editorials right along with him.

Although his battles with KSL’s editorial board became the stuff of legend, he managed -- thanks to his personal charisma and powers of persuasion -- to both keep his job and influence the positions that KSL adopted on the most important issues of the day. Despite his differences with the higher-ups, Wes was truly fond of them.

I enjoyed researching and writing editorials at first, but it quickly became tiresome. To say, “KSL condemns the……..” or “KSL hopes all citizens will………” or “KSL applauds the children whose pennies made such a difference…..,” began to seem like a pointless exercise. It made me feel impotent, and I don't like that. Very little that we wrote, no matter how sensible and well-documented, had any effect on anything. So I remained in the job for the college credit, the paycheck and the priceless opportunity to get to know my very first Great Man.

STROLLING, STARRY-EYED, WITH CARY GRANT

As a 19-year-old, I was awe-struck by the fact that I got to hang out with Wes for three half-days a week. It was like having Cary Grant move in with you and become your bosom friend. He was such a bon vivant with so much savoir faire! (my French was finally coming in handy) He was an aristocrat, and he was a legend. The word “panache” was invented for this man! He was the romantic lead in a period piece about the glory days of the British Empire. He was my hero.

Walking around downtown with him, mulling ideas for our next editorial series, one would have thought that he had royal blood and royal powers. People descended upon us from all directions on Social Hall Avenue and on South Temple, as if to kiss his ring. He was very amused by all the adulation, and I think he secretly believed he deserved every damn bit of it. He was not at all oblivious to his magnetism.

We always wound up at the University Club, high up, overlooking the city, such as it was. He ordered two coffees and two massive sweet rolls, drenched in icing, with two pats of melted butter on top of each. My god -- and I ate it! How did that happen? When you were with dear Wesley, there was a devil-may-care contagion that occurred. You were in a zone of Magic in which calories did not count. (When we got back to the office, he always offered me a sweet, herbal pastille from the tin on his desk, just to get more sugar into me, and I never refused one.) To me, everything was in a shimmer, I felt so privileged to be his friend. I think he would have regarded me as his daughter, if he weren’t so profoundly in love with his actual daughter. He never failed to get teary-eyed, just mentioning her name.

So he told me his feelings for me were “avuncular.” That was just one of hundreds of words he used over the years that I had to ask him to define. He said, “Don’t mind me if I get a bit ribald.“ If it had been anyone else, I would have thought he was showing off. But Wes wasn’t -- he loved language, as I do, and he always wanted to use the perfect word, no matter how obscure it might be to the unwashed masses.

LONDON CALLING

After my third year of college, I was awarded a grant to spend the summer in London, studying the impact that immigration was having on British society.

Wes had been reared in England and went to the prestigious Queen Elizabeth’s Hospital boarding school for boys in Bristol, which is pictured below. He loved London and was delighted that I would experience his old stomping grounds.

As a going-away gift, he gave me a beautiful Montblanc fountain pen, dark navy blue with gold trim. I had always admired his “fine writing instruments,” as he called them, and he knew I would be doing a lot of note-taking during my stay. He also gave me an elegant old cigarette lighter that he no longer needed. We both enjoyed the solid sound it made when it was opened and closed, the same sort of sound that a Mercedes-Benz door makes: a click of cultivation. Wes surrounded himself with tasteful, beautifully made products, from his clothing to his extraordinary sound system at home, to his artwork and even his personal care products. It wasn’t a conceit; he simply loved quality and believed it was well worth paying for.

He insisted that while in London I “indulge in” a breakfast cereal, Famila Swiss Müesli, which at that time was unheard of here in the States, and wrote me a list of several brands of biscuits, chocolate and marmalade that were de rigueur when abroad. Of course, he added, it was “imperative” that I don proper attire for British High Tea, and then partake of it at Harrod’s, the world-famous department store. “I would strongly advise against their sweets,” he counseled me. “Watercress sandwiches would provide a richer and more authentic experience.”

There was more:

“You simply must find a burnished old pub somewhere,” he said, “and demand Pimm’s Cup with a slice of cucumber. Insist on one ice cube -- no more!”

He insisted that while in London I “indulge in” a breakfast cereal, Famila Swiss Müesli, which at that time was unheard of here in the States, and wrote me a list of several brands of biscuits, chocolate and marmalade that were de rigueur when abroad. Of course, he added, it was “imperative” that I don proper attire for British High Tea, and then partake of it at Harrod’s, the world-famous department store. “I would strongly advise against their sweets,” he counseled me. “Watercress sandwiches would provide a richer and more authentic experience.”

There was more:

“You simply must find a burnished old pub somewhere,” he said, “and demand Pimm’s Cup with a slice of cucumber. Insist on one ice cube -- no more!”

What yummy advice, dear Wes. Pimm’s Cup, a tea-colored, gin-based drink containing quinine and a secret mixture of herbs and citrus, made American cocktails such as Whiskey Sours and Tom Collins seem silly and childishly sweet.

I felt like a true woman of the world, (although I was only 20 years old) sitting in that place that was aglow with golden wood and antique fixtures, silently toasting my friend as I sipped the pleasantly bitter libation while smoking a French cigarette (Gauloise was an excellent brand -- made with black Russian tobacco. It was favored by Jean-Paul Sartre and Pablo Picasso, so naturally, I favored it as well. The last factory in France making Gauloise cigarettes shut down in 1985 as “softer” and “sweeter” American cigarettes took over the market. How typical! Just as McDonald’s was blighting the felicitous avenues of Paris. Viva l‘Amerique!)

I got a letter from Wes every week, filled with colorful accounts of his exasperating battles at KSL, his ruminations on the meaning and impact of beauty, his despair over the cheapening of American culture, and his sentiments about mortality.

I asked him if he believed in life after death.

“I certainly won’t go on forever as Wesley Gordon Bowen, if that’s what you mean,” he scoffed. “How boring! How preposterous! How callously uncivilized! But I do expect to join a great, undifferentiated consciousness out there, somewhere. There is a part of each of us that shall not be extinguished.”

He could make you laugh and move you to tears at the same time.

I got in over my head that summer, and my research took me to places I should never have gone by myself, if at all. Gang rule was in effect, and there seemed to be no police presence. I was the victim of a crime that left me shattered, physically and emotionally. I didn’t want to traumatize my parents, but I had to call someone, so I called Wes.

MY HERO FLIES TO THE RESCUE

I had just been released from the hospital. I was sobbing. I could hardly talk. He didn’t ask for any details -- he just knew that I needed someone to come and bring me home.

So that is what he did, in the grandest and most decisive demonstration of friendship I’ve ever known. He arranged to take care of some business in London -- business that did justify the trip -- and before I knew it, he was there.

We couldn’t leave for four days, so I gave Wes my room and slept with my two roommates, Jane and Jenny. Both were very attractive high-end corporate secretaries, but they demonstrated to me over and over again how superior British schools are to ours. They hadn’t even gone to college, yet I felt that they had a much greater knowledge of history, literature and the arts than I did. They also had a poise and wide-ranging competence that I had never witnessed in women as young as they.

One of Wes’s favorite anecdotes arose out of his stay in my room. The morning after he arrived, he got up and tried to put on his pants. After much yanking and profanity, he realized that they were my identical Farah trousers. For the rest of his life, whenever we were around other people, he couldn’t resist saying, “Did I ever tell you about the time I almost got into Sylvia’s pants?” He never got tired of it. I certainly did, but this was a very minor price to pay for our acquaintanceship.

He tried valiantly to cheer me up, which was the only foolish thing he ever did as long as I knew him. There is no cheering up someone who is in a an acute state of shock and grief. He took me sightseeing, which is something I hadn’t done on my own, so I got to see Westminster Abbey (pictured above), Piccadilly Circus, Buckingham Palace and other sites of note. I’m glad to have those memories, but at the time it was a nightmare just to be in public. I felt as if I had been administered a heavy-duty central nervous system depressant. I felt dead, and I wished I felt more dead.

He tried valiantly to cheer me up, which was the only foolish thing he ever did as long as I knew him. There is no cheering up someone who is in a an acute state of shock and grief. He took me sightseeing, which is something I hadn’t done on my own, so I got to see Westminster Abbey (pictured above), Piccadilly Circus, Buckingham Palace and other sites of note. I’m glad to have those memories, but at the time it was a nightmare just to be in public. I felt as if I had been administered a heavy-duty central nervous system depressant. I felt dead, and I wished I felt more dead.

WES TURNS CONVERSATION INTO A CINEMATIC EVENT

One night, West took me, my roommates and two male African-American friends of mine -- one a neighborhood organizer, the other a math genius who was working for Sperry-Rand -- out for drinks and dinner. I could feel an anxiety attack coming on as we settled into a booth. Claustrophobia, panic, flashbacks. One of my roommates gave me the first sedative I’d ever had, excluding whatever they gave me in the hospital, and pretty soon, I was floating in what seemed to be a tingly pink cloud of peppermint icing.

Wes was in great form that night -- actually, he was always in great form when he had an audience, even of one. He regaled us with stories of his youthful pranks at boarding school, his escapades in London, and his inadvertent heroics when he was with the British military as a commander in both artillery and paratrooper regiments during World War II. He had extended duty in India, where his job was to oversee the “inspection” of prostitutes, to ensure that they weren’t infected with any venereal diseases.

“A man with any decency would have lost his sexual appetites forever after scrutinizing one hideously overused perineal area after another,” he said. “Pudendal canals, ischial tuberosities -- my God, it was monstrous. But one’s heart had to go out to those poor girls.”

“A man with any decency would have lost his sexual appetites forever after scrutinizing one hideously overused perineal area after another,” he said. “Pudendal canals, ischial tuberosities -- my God, it was monstrous. But one’s heart had to go out to those poor girls.”

Wes grew to love India and its people, and he would develop personal and business ties there that endured throughout his life.

When Wes was in “performance mode,” he assumed a persona that a Monty Python fan would find irresistible. He was a skilled verbal swordsman who physically embodied the tone of his stories. He furrowed his brow, worked his lips into an emblem of haughtiness and wry exasperation, and recounted his life experiences with exquisite detail, mind-boggling juxtapositions and his hallmark cynicism. He glowered, he was bilious, he lifted his chin and looked down his nose with utter contempt when recalling the fools he had encountered during his March Through Time.

His impersonations of each of his characters were hilarious, and it seemed that his face could assume the qualities of an infinite number of uppity, condescending, frivolous, pretentious, misguided, clueless, gluttonous, predatory people.

Wes loved to play the role of misanthrope. He seemed to become a caricature of himself to ensure that he would be amusing, and he always was. He acquired the mannerisms of a sputtering blowhard, an arrogant aristocrat, a punctilious civil servant or a reckless, ravenous Captain of Industry.

He tried not to laugh as he embodied these characters for our entertainment, but he couldn’t help it. The fact that he was trying so hard not to laugh, to remain in the full hauteur of his character, made his crack-ups all the funnier. He was a master raconteur, and he bloody well knew it, to use one of his favorite expressions. And if you were to say, “Wes, you’re the greatest storyteller ever!” he would respond, “Balls!”

WESLEY’S HEARTBREAKING HEARTACHE

Within a few months of returning to Salt Lake City, I fled to New York in an attempt to start my life anew. I was gone for 10 years, and Wes never let our correspondence lag. Although he harbored deep affection and respect for his wife, they had gotten a divorce, and his loneliness brought a new melancholy to his letters.

He had always been a romantic -- in the way you read about in old British novels -- a man who regarded courtship as an art form and physical chemistry as one of the ecstatic pinnacles of human experience.

He regarded himself as a lover -- a very ardent, generous one -- and he wanted someone to love. He was so full of love -- he so needed a vessel in which to pour it -- that he seemed to be in physical as well as emotional pain without it.

Wes was a connoisseur of women in the way that he was a connoisseur of everything beautiful. To him, women were “luscious,” “creamy” and “delicious” -- adjectives that always made me want some pudding. Women were to be tasted and savored, adored and gallantly wooed. They were dewy flowers that required gentle care and cultivation.

A love affair was something that must be “conducted,” with a keen sensitivity to rhythm and pacing, to the delicate conjuring of harmonies, and to the patiently calibrated crescendo.

Wes wanted a love to which he could surrender, the way he joyfully surrendered to gravity as he flew down the mountain on his skis.

He made a few attempts at building such a relationship, a couple of them quite promising for awhile, but he soon resigned himself to a life in which longing tinged everything.

Whenever I came home from New York to visit, I spent time with Wes. He was still in love with so many things -- poetry, skiing, golf, technology, history, jazz, classical music and travel -- but his desire for a life partner remained the backdrop of his existence.

I ached for him. Loneliness in someone you love is the saddest thing in the world.

He wasn’t alone, by any means. He had several very good friends and lots of pretty good friends and legions of fond acquaintances and many thousands of adoring fans.

What he valued most though, in all the years I knew him, was his family. His ex-wife, his four sons and his daughter were always his highest priority. He loved them, and he loved being with them, and it was toward them that he expressed the most poignant tenderness. His daughter, who was now a wife and mother, was still his “little girl.”

I once asked him if he had to pay alimony to his ex-wife, and he emphatically replied: “I want to support her. She is the finest person I have ever known. God knows she deserves everything I give her and more.”

SOME GOOD HANG TIME WITH DEAR WESCULARITY

“Sorry, luv, I’m in the midst of my toilette. Can I ring you back in a few?”

I never stopped getting a kick out of the way Wes expressed himself.

When he did call back, I said, in true Wesley fashion: “Of what does your precious toilette consist?"

“Sylvia, Sylvia, you are far too bright not to know this: It is the ritualized performance of everything one does to make oneself presentable to the world,” he explained.

“Like lots of Aramis?” I kidded him.

“Tons,” he retorted. “It’s my signature scent.”

I had moved back to Salt Lake City and was working at the newspaper. It was great to be able to spend time with him again. He skewered my devotion to print journalism, arguing, “You should be in television. That’s where everything is headed.”

Now that everything seems to be headed for the Internet, I think he would approve of my presence here, even though he might dismiss my blog as “a piddling, aimless venture, entirely unworthy of your time.”

When Wes went shopping, he insisted on doing it the European way: going to shops, not stores. So we went to the bakery for bread, the cheese shop for cheese, Granato’s for fresh pasta, pancetta and olive oil, and to Mexican, Asian and Indian shops for produce, grains, spices and condiments.

Every place we entered, they all knew Wes -- they even called fellow employees from the back rooms to come out and greet their dear prince. Everyone brightened and joined in the banter -- he always created a nice little uproar -- and he was really in his element, shooting the breeze and creating a whole new atmosphere single-handedly. He had a blast, driving about in his spotless “motor car,” just spreading his sparkle everywhere.

Every place we entered, they all knew Wes -- they even called fellow employees from the back rooms to come out and greet their dear prince. Everyone brightened and joined in the banter -- he always created a nice little uproar -- and he was really in his element, shooting the breeze and creating a whole new atmosphere single-handedly. He had a blast, driving about in his spotless “motor car,” just spreading his sparkle everywhere.

Wes knew lots of powerful people and lots of celebrities, but I believe it was common, humble, hard-working people for whom he felt the greatest affection. He enjoyed men and women alike, but occasionally he couldn’t resist making a remark such as, “Did you take note of that young lady’s bottom? It was delicious!”

I told him more than once that the use of “bottom” and “delicious” in the same breath turned my stomach a bit, but he couldn’t, or chose not to, restrain himself. He did intermittently change the word to “bum,” but that didn’t really help matters.

We occasionally went to lunch at one of his old favorites: Lamb’s Grill, Le Parisien, The Mikado or Porters and Waiters (soul food, across from the train station). Each entrance we made caused a commotion as word spread that Wes Bowen had arrived. Waiters, chefs and owners emerged to pay their respects, and there were always murmurs among the seated patrons as His Eminence and I were escorted to a table. Le Parisien’s Max Mercier, who seemed to take utter delight in Wes’s anecdotes and provocative questions, died three months before Wes of cancer.

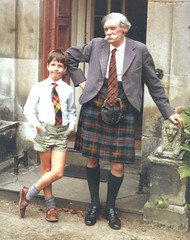

One exception to Wes’s preference for the Common Man was his intense and greatly enriching relationship with Sir Iain Moncrieffe of that Ilk -- of what “ilk” I never quite understood. Here is Sir Iain:

Sir Iain, who had served as attaché at the British embassy in Moscow after getting a degree at Oxford, lived in a magnificent castle in Scotland. Every couple of years, Wes stayed for a week or two with Sir Iain and his wife, Lady Hermione, and Wes was as charmed by the former British officer as the rest of us were charmed by Wes. A self-confessed "incorrigible snob," which is also how Wes characterized himself, Sir Iain -- like Wes -- had an encyclopedic knowledge of history and culture. He was also a world-recognized expert on heraldry and peerage, whatever that is. The two of them would go stomping among the bogs for hours, to “take some air,” and “bring colour to the cheeks,” before retiring to the Great Room for symphonic music and a glass of Scotch prior to a grand banquet in the Dining Hall. Wes loved Sir Iain and was devastated when he died in 1985. Here is Sir Iain's castle, as drawn by his young son:

Wes often called me to “chat,” but these were generally not conversations -- they consisted of epic stream-of-consciousness monologues. Wes let his mind unfurl like a roll of silk, and I think he probably forgot whom he was talking to half the time. He got lost in the baroque paradise of his own mind and kind of went into a trance of reminiscence and reverie. Wes’s long phone conversations were mentioned at his funeral, by former Salt Lake Mayor Rocky Anderson, I believe -- and the ripple of amusement in the packed chapel suggested that I was far from the only one who was graced by his telephonic bestowances.

Whenever Wes called, I lay down on the carpet and closed my eyes so I could join in his rhapsodic communion. I can’t sit for extended periods, and the calls were almost always extended.

Sometimes he called, though, just to read me a poem. When he read Pablo Neruda’s love poetry, he conveyed such deep anguish and longing, such intensity and grief, that it made me want to weep. I felt that these recitations were a sort of purging for Wes of his pain at not having a lover.

He always ended his calls the same way. “I hope you know that you are very dear to me.”

I wish I had said something besides, “I know, Wes. Thank you.”

I was too shy about expressing emotion verbally, but if I had, he probably would have said something like, “That is the most vile heap of inglorious sentimentality to which I have ever been witness!”

Or he might have characterized my expression of overwhelming affection and sense of privilege as “diarrhea of the mouth,” which was another of his favorite figures of speech.

WESLEY, GLISTENING

I had never seen Wes perspire before. He was in his basement, engaged in a rather grueling weight-training session, and I have no memory of how I happened to be there, but I was pleased to witness yet another aspect of his life.

I knew he loved his golf, tennis and skiing, but I would have never dreamed that he was a pumper of iron. He was pink and shimmery, wearing a sleeveless undershirt and sweatpants (I had never seen him when he wasn’t all turned out in very dapper, beautifully tailored business attire or -- at home -- in handsome sweaters and slacks). In between grunts, he bestowed upon me a compelling, nuanced interpretation of Machiavelli’s works, and explained how his concepts had been utterly bastardized by others, just as Freud’s had been.

“I’m hungry,” I said.

“How do you feel about tomatillos?” he asked, toweling off his chest and back.

“I’ve never heard of them,” I replied.

“Excellent! You’re in for a treat. I’ll leap into the bath, and then I’ll whip us up a luncheon to remember,” he promised.

Wes was positively turgid with vitality, no matter the situation or the time of day or night. The way in which he spoke, breathed and moved revealed an abundance of life-force.

CURRYING FAVOR

He prepared several memorable meals for us over the years, but the most outstanding was a massive pot of lamb curry, which took hours to make. I reminded him that I was vegetarian, but I would make the compromise of ingesting some of the lamb “juice” if he didn’t mind my picking out the chunks of meat.

I have only known one other person -- a splendid fellow from Grenada -- who could navigate the preparation of a complex meal while simultaneously engaging in spirited conversation.

Wes was lithe, he was nimble, he was positively insouciant as he chopped, blanched, caramelized, pulverized, and I don’t remember what else, to create his magical concoction. It had coconut milk in it, and golden raisins, and ground toasted cashews and a slew of colorful Indian spices.

While it simmered, he offered me a glass of wine.

“Alcohol,“ he always noted, “is a splendid social lubricant.”

He tried to persuade me that my education would be appallingly incomplete until I committed myself to reading “The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon.

“My God, it’s six volumes, Wes,” I moaned. “Can’t you just summarize it for me?”

I was kidding, of course, but he seemed enamored with the idea.

“I’ll turn on the rice, and we can begin this minute!” he beamed. “You‘ll have to come for dinner every night for the next several years.”

What we actually did instead was to listen to music. Wes was determined to teach me “how to listen,” which sounded insulting at first but turned out to be very enriching. Almost every time we were together, he turned up his excellent sound system and explained to me what was happening and what it meant and how it was intended to make me feel.

Wes listened to music -- whether jazz or classical -- with his whole body. It filled him with so much emotion that he could barely contain himself.

GOODBYE

When one of Wes’s best friends told me that Wes had been found face-down on his bed, having died of a heart attack, I was overwhelmed with grief -- not just that he died, but that he died alone. I wondered if he had lain there, feeling the explosion in his chest, and was unable to reach the phone. Wes: I am so sorry.

I don’t go to funerals, but I did try to make it through the service held for Wes. I was crying from the moment I saw his picture on the stage, but I was able to do it soundlessly and not create a distraction. Finally, though, I was so congested and wracked with grief that I couldn’t breathe, so I slipped out the back. On the way out, I saw tables arrayed with pictures of Wes, from his youth up to the present. When I saw the photos of him with his grandchildren, that is when the full-fledged sobbing began. I had never seen him look so joyful, so serene and so tender in all our years of friendship. He was soft and aglow. He looked even more angelic than the children.

I love you, Wesley, so much. I would say that I miss you, but you are still very much in my life.

I felt like a true woman of the world, (although I was only 20 years old) sitting in that place that was aglow with golden wood and antique fixtures, silently toasting my friend as I sipped the pleasantly bitter libation while smoking a French cigarette (Gauloise was an excellent brand -- made with black Russian tobacco. It was favored by Jean-Paul Sartre and Pablo Picasso, so naturally, I favored it as well. The last factory in France making Gauloise cigarettes shut down in 1985 as “softer” and “sweeter” American cigarettes took over the market. How typical! Just as McDonald’s was blighting the felicitous avenues of Paris. Viva l‘Amerique!)

I got a letter from Wes every week, filled with colorful accounts of his exasperating battles at KSL, his ruminations on the meaning and impact of beauty, his despair over the cheapening of American culture, and his sentiments about mortality.

I asked him if he believed in life after death.

“I certainly won’t go on forever as Wesley Gordon Bowen, if that’s what you mean,” he scoffed. “How boring! How preposterous! How callously uncivilized! But I do expect to join a great, undifferentiated consciousness out there, somewhere. There is a part of each of us that shall not be extinguished.”

He could make you laugh and move you to tears at the same time.

I got in over my head that summer, and my research took me to places I should never have gone by myself, if at all. Gang rule was in effect, and there seemed to be no police presence. I was the victim of a crime that left me shattered, physically and emotionally. I didn’t want to traumatize my parents, but I had to call someone, so I called Wes.

MY HERO FLIES TO THE RESCUE

I had just been released from the hospital. I was sobbing. I could hardly talk. He didn’t ask for any details -- he just knew that I needed someone to come and bring me home.

So that is what he did, in the grandest and most decisive demonstration of friendship I’ve ever known. He arranged to take care of some business in London -- business that did justify the trip -- and before I knew it, he was there.

We couldn’t leave for four days, so I gave Wes my room and slept with my two roommates, Jane and Jenny. Both were very attractive high-end corporate secretaries, but they demonstrated to me over and over again how superior British schools are to ours. They hadn’t even gone to college, yet I felt that they had a much greater knowledge of history, literature and the arts than I did. They also had a poise and wide-ranging competence that I had never witnessed in women as young as they.

One of Wes’s favorite anecdotes arose out of his stay in my room. The morning after he arrived, he got up and tried to put on his pants. After much yanking and profanity, he realized that they were my identical Farah trousers. For the rest of his life, whenever we were around other people, he couldn’t resist saying, “Did I ever tell you about the time I almost got into Sylvia’s pants?” He never got tired of it. I certainly did, but this was a very minor price to pay for our acquaintanceship.

WES TURNS CONVERSATION INTO A CINEMATIC EVENT

One night, West took me, my roommates and two male African-American friends of mine -- one a neighborhood organizer, the other a math genius who was working for Sperry-Rand -- out for drinks and dinner. I could feel an anxiety attack coming on as we settled into a booth. Claustrophobia, panic, flashbacks. One of my roommates gave me the first sedative I’d ever had, excluding whatever they gave me in the hospital, and pretty soon, I was floating in what seemed to be a tingly pink cloud of peppermint icing.

Wes was in great form that night -- actually, he was always in great form when he had an audience, even of one. He regaled us with stories of his youthful pranks at boarding school, his escapades in London, and his inadvertent heroics when he was with the British military as a commander in both artillery and paratrooper regiments during World War II. He had extended duty in India, where his job was to oversee the “inspection” of prostitutes, to ensure that they weren’t infected with any venereal diseases.

Wes grew to love India and its people, and he would develop personal and business ties there that endured throughout his life.

When Wes was in “performance mode,” he assumed a persona that a Monty Python fan would find irresistible. He was a skilled verbal swordsman who physically embodied the tone of his stories. He furrowed his brow, worked his lips into an emblem of haughtiness and wry exasperation, and recounted his life experiences with exquisite detail, mind-boggling juxtapositions and his hallmark cynicism. He glowered, he was bilious, he lifted his chin and looked down his nose with utter contempt when recalling the fools he had encountered during his March Through Time.

His impersonations of each of his characters were hilarious, and it seemed that his face could assume the qualities of an infinite number of uppity, condescending, frivolous, pretentious, misguided, clueless, gluttonous, predatory people.

Wes loved to play the role of misanthrope. He seemed to become a caricature of himself to ensure that he would be amusing, and he always was. He acquired the mannerisms of a sputtering blowhard, an arrogant aristocrat, a punctilious civil servant or a reckless, ravenous Captain of Industry.

He tried not to laugh as he embodied these characters for our entertainment, but he couldn’t help it. The fact that he was trying so hard not to laugh, to remain in the full hauteur of his character, made his crack-ups all the funnier. He was a master raconteur, and he bloody well knew it, to use one of his favorite expressions. And if you were to say, “Wes, you’re the greatest storyteller ever!” he would respond, “Balls!”

WESLEY’S HEARTBREAKING HEARTACHE

Within a few months of returning to Salt Lake City, I fled to New York in an attempt to start my life anew. I was gone for 10 years, and Wes never let our correspondence lag. Although he harbored deep affection and respect for his wife, they had gotten a divorce, and his loneliness brought a new melancholy to his letters.

He had always been a romantic -- in the way you read about in old British novels -- a man who regarded courtship as an art form and physical chemistry as one of the ecstatic pinnacles of human experience.

He regarded himself as a lover -- a very ardent, generous one -- and he wanted someone to love. He was so full of love -- he so needed a vessel in which to pour it -- that he seemed to be in physical as well as emotional pain without it.

Wes was a connoisseur of women in the way that he was a connoisseur of everything beautiful. To him, women were “luscious,” “creamy” and “delicious” -- adjectives that always made me want some pudding. Women were to be tasted and savored, adored and gallantly wooed. They were dewy flowers that required gentle care and cultivation.

A love affair was something that must be “conducted,” with a keen sensitivity to rhythm and pacing, to the delicate conjuring of harmonies, and to the patiently calibrated crescendo.

Wes wanted a love to which he could surrender, the way he joyfully surrendered to gravity as he flew down the mountain on his skis.

He made a few attempts at building such a relationship, a couple of them quite promising for awhile, but he soon resigned himself to a life in which longing tinged everything.

Whenever I came home from New York to visit, I spent time with Wes. He was still in love with so many things -- poetry, skiing, golf, technology, history, jazz, classical music and travel -- but his desire for a life partner remained the backdrop of his existence.

I ached for him. Loneliness in someone you love is the saddest thing in the world.

He wasn’t alone, by any means. He had several very good friends and lots of pretty good friends and legions of fond acquaintances and many thousands of adoring fans.

What he valued most though, in all the years I knew him, was his family. His ex-wife, his four sons and his daughter were always his highest priority. He loved them, and he loved being with them, and it was toward them that he expressed the most poignant tenderness. His daughter, who was now a wife and mother, was still his “little girl.”

I once asked him if he had to pay alimony to his ex-wife, and he emphatically replied: “I want to support her. She is the finest person I have ever known. God knows she deserves everything I give her and more.”

SOME GOOD HANG TIME WITH DEAR WESCULARITY

“Sorry, luv, I’m in the midst of my toilette. Can I ring you back in a few?”

I never stopped getting a kick out of the way Wes expressed himself.

When he did call back, I said, in true Wesley fashion: “Of what does your precious toilette consist?"

“Sylvia, Sylvia, you are far too bright not to know this: It is the ritualized performance of everything one does to make oneself presentable to the world,” he explained.

“Like lots of Aramis?” I kidded him.

“Tons,” he retorted. “It’s my signature scent.”

I had moved back to Salt Lake City and was working at the newspaper. It was great to be able to spend time with him again. He skewered my devotion to print journalism, arguing, “You should be in television. That’s where everything is headed.”

Now that everything seems to be headed for the Internet, I think he would approve of my presence here, even though he might dismiss my blog as “a piddling, aimless venture, entirely unworthy of your time.”

When Wes went shopping, he insisted on doing it the European way: going to shops, not stores. So we went to the bakery for bread, the cheese shop for cheese, Granato’s for fresh pasta, pancetta and olive oil, and to Mexican, Asian and Indian shops for produce, grains, spices and condiments.

Wes knew lots of powerful people and lots of celebrities, but I believe it was common, humble, hard-working people for whom he felt the greatest affection. He enjoyed men and women alike, but occasionally he couldn’t resist making a remark such as, “Did you take note of that young lady’s bottom? It was delicious!”

I told him more than once that the use of “bottom” and “delicious” in the same breath turned my stomach a bit, but he couldn’t, or chose not to, restrain himself. He did intermittently change the word to “bum,” but that didn’t really help matters.

We occasionally went to lunch at one of his old favorites: Lamb’s Grill, Le Parisien, The Mikado or Porters and Waiters (soul food, across from the train station). Each entrance we made caused a commotion as word spread that Wes Bowen had arrived. Waiters, chefs and owners emerged to pay their respects, and there were always murmurs among the seated patrons as His Eminence and I were escorted to a table. Le Parisien’s Max Mercier, who seemed to take utter delight in Wes’s anecdotes and provocative questions, died three months before Wes of cancer.

One exception to Wes’s preference for the Common Man was his intense and greatly enriching relationship with Sir Iain Moncrieffe of that Ilk -- of what “ilk” I never quite understood. Here is Sir Iain:

Whenever Wes called, I lay down on the carpet and closed my eyes so I could join in his rhapsodic communion. I can’t sit for extended periods, and the calls were almost always extended.

Sometimes he called, though, just to read me a poem. When he read Pablo Neruda’s love poetry, he conveyed such deep anguish and longing, such intensity and grief, that it made me want to weep. I felt that these recitations were a sort of purging for Wes of his pain at not having a lover.

He always ended his calls the same way. “I hope you know that you are very dear to me.”

I wish I had said something besides, “I know, Wes. Thank you.”

I was too shy about expressing emotion verbally, but if I had, he probably would have said something like, “That is the most vile heap of inglorious sentimentality to which I have ever been witness!”

Or he might have characterized my expression of overwhelming affection and sense of privilege as “diarrhea of the mouth,” which was another of his favorite figures of speech.

WESLEY, GLISTENING

I had never seen Wes perspire before. He was in his basement, engaged in a rather grueling weight-training session, and I have no memory of how I happened to be there, but I was pleased to witness yet another aspect of his life.

I knew he loved his golf, tennis and skiing, but I would have never dreamed that he was a pumper of iron. He was pink and shimmery, wearing a sleeveless undershirt and sweatpants (I had never seen him when he wasn’t all turned out in very dapper, beautifully tailored business attire or -- at home -- in handsome sweaters and slacks). In between grunts, he bestowed upon me a compelling, nuanced interpretation of Machiavelli’s works, and explained how his concepts had been utterly bastardized by others, just as Freud’s had been.

“I’m hungry,” I said.

“How do you feel about tomatillos?” he asked, toweling off his chest and back.

“I’ve never heard of them,” I replied.

“Excellent! You’re in for a treat. I’ll leap into the bath, and then I’ll whip us up a luncheon to remember,” he promised.

Wes was positively turgid with vitality, no matter the situation or the time of day or night. The way in which he spoke, breathed and moved revealed an abundance of life-force.

CURRYING FAVOR

He prepared several memorable meals for us over the years, but the most outstanding was a massive pot of lamb curry, which took hours to make. I reminded him that I was vegetarian, but I would make the compromise of ingesting some of the lamb “juice” if he didn’t mind my picking out the chunks of meat.

I have only known one other person -- a splendid fellow from Grenada -- who could navigate the preparation of a complex meal while simultaneously engaging in spirited conversation.

Wes was lithe, he was nimble, he was positively insouciant as he chopped, blanched, caramelized, pulverized, and I don’t remember what else, to create his magical concoction. It had coconut milk in it, and golden raisins, and ground toasted cashews and a slew of colorful Indian spices.

While it simmered, he offered me a glass of wine.

“Alcohol,“ he always noted, “is a splendid social lubricant.”

He tried to persuade me that my education would be appallingly incomplete until I committed myself to reading “The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon.

“My God, it’s six volumes, Wes,” I moaned. “Can’t you just summarize it for me?”

I was kidding, of course, but he seemed enamored with the idea.

“I’ll turn on the rice, and we can begin this minute!” he beamed. “You‘ll have to come for dinner every night for the next several years.”

What we actually did instead was to listen to music. Wes was determined to teach me “how to listen,” which sounded insulting at first but turned out to be very enriching. Almost every time we were together, he turned up his excellent sound system and explained to me what was happening and what it meant and how it was intended to make me feel.

Wes listened to music -- whether jazz or classical -- with his whole body. It filled him with so much emotion that he could barely contain himself.

GOODBYE

When one of Wes’s best friends told me that Wes had been found face-down on his bed, having died of a heart attack, I was overwhelmed with grief -- not just that he died, but that he died alone. I wondered if he had lain there, feeling the explosion in his chest, and was unable to reach the phone. Wes: I am so sorry.

I love you, Wesley, so much. I would say that I miss you, but you are still very much in my life.